During the past two years theatre and performance art spaces and training programs have been forced to close down, across the United States and Europe. Recently, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) abandoned its live theatre festival; the esteemed National Theatre Conservatory in Denver is phasing out its graduate program; and, highly regarded non-profit companies like the Pasadena Playhouse are disintegrating. Even a remarkably affluent community like Nantucket, MA – where ‘millionaires mow the lawns of billionaires’ – has failed to protect its tradition-in-the-making of seasonal theatre. Seaside Shakespeare, founded by actress, producer and director, Susan

McGinnis, has had to suspend its programming for an entire on an island which prides itself in being a National Historic District. In other words, even proximity to absurd amounts of money does not signify a community possessing the foresight to preserve its intangible heritage. In Europe, a similar dissolution of support for non-tangible cultural patrimony is taking place. Only last week, a Dutch choreographer friend, Edd Schouten, told me that his program at Daghdha Dance Company, in Co. Limerick, Ireland is “struggling for financial survival.”Now, imagine a group of young theatre artists who, in the middle of the worst economic downturn since the Depression, has the fortitude (or shall we say the chutzpah) to start a multimedia production company at the heart of the intensely competitive entertainment capital of the world, in Los Angeles.

Psittacus Productions, however, hardly resembles our vision of what a start-up performance arts venture ought to look like. The company founders’ tri-coastal (London, New York, Los Angeles) team have made their marks on four continents, including 49 states across the US. Robert Richmond of the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama; Louis Butelli of the prestigious Aquila Theatre Company; and, the dynamic dramaturg, Chas LiBretto comprise Psittacus’ founding members. Along with other collaborative partners, the Productions team have nearly a century worth of experience as: writers, actors, directors, performers, composers and choreographers.

The rich theatrical heritage and vast body of experience of Psittacus’ creative members promise to inject much-needed life and vibrancy into the vanishing world of Classical Theatre. The company’s mission is “to create innovative theatre art to share with the community, and to investigate the ways in which modern life and technology affect the way we tell stories.” In other words, Psittacus has set out to unveil and stage the corpus of our collective memories – as embodied in classic Western literature – in the highly stylized and aesthetized form of theatre via Web 3.0, smart phones, and other technological apparatus.

This is, fundamentally, what differentiates Psittacus Productions from nearly every other performance art group that uses aspects of multimedia: the company produces performative works which begin with technology. Their art is grounded in the principle to create narrative that is expressly and simultaneously crafted for the stage and the Internet. Psittacus’ mission is to “allow the art form of theatre to truly reflect the experience of being alive at the start of the 21st century,” says Butelli. As a performance laboratory, the company engages “the power of social networking and new technologies to create an essentially virtual theatre and production company.”

As an artistic genome par excellence, theatre’s primary function is to explore the collective intelligence and artistic expression of individual creators – writers, actors, designers, choreographers – and the ways in which they relate to one another as well as to a greater whole.

Unlike most traditional art forms where artists act as solitary figures basing the majority of their work on singular vision(s), “theatre is that rare animal in the arts.” Butelli explains that the medium is “a fully collaborative form, wherein a company of players who know each others’ work, strengths and weaknesses can grow and flourish.” The collective improvisatory nature of theatre, too, allows for new and unexpected encounters and results to develop.

Even for creatures known for their mimetic abilities, “social interaction, reference, and full contextual experience are important factors in learning to produce and comprehend an allospecific code.” No, this University of Arizona study was not about theatre performers but about Psittacus Erithacus – that life form after which the company is named. “It’s pronounced ‘SIT-ih-kuss'”!

The mother of all collective intelligence arts, theatre is a mechanism whose primary functions are to identify and (re)discover our communal heritage – our collective memories. In this sense, Psittacus’ mission to connect the future of our lives and how we relate it to our present and past lies at the roots of modern (16th century-present) theatre.

Few young performing arts groups can rival the knowledge that the founders of Psittacus possess of the theatre of the Renaissance. As a matter of fact, Butelli and LiBretto met while working at Susan McGinnis’ Seaside Shakespeare, on Nantucket, in 2008. A decade ago, The New York Times hailed Richmond’s directorial work on a production of Cyrano De Bergerac (2000) to have “set a high standard for charm and invention.” The NYT’s D.J.R Bruckner, equally, reveled in Butelli’s performance in the Comedy of Errors asserting that he possess “the timing and precision of a dancer, [who] might be made of rubber.” The DC Theatre Scene called him “the fabulous Louis Butelli” who played his part (Grumio) in Taming of the Shrew “to perfection.”

More than half a century before William Shakespeare wrote his Tragedy of Macbeth (in 1604-11) – whose adaptation marks Psittacus’ world premier performance – the great Renaissance thinker, Giulio Camillo Delminio (1480-1544), published the canonical Idea del Theatro. Camillo envisioned his teatro della memoria in the future tense since it was yet to be built. Based on the ancient ‘art of memory,’ Camillo’s teatro was a virtual mnemonic space that embodied all the knowledge in the world. The actor/participant would take position in the middle of the stage and seek to grasp all “eternal truths” that depicted “the various stages of creation, from the first cause through the angels, the planetary spheres, and down to man.” This order of ‘eternal truths’ was registered through a Cosmologically Wide Web of link systems that was based on various tightly or loosely related loci (places or spaces), in a simulated environment. Simulated, since, first, Camillo’s theatre had not yet been constructed; and second, in its Classical genesis, the practice of the ‘art of memory’ takes place in an imaginary spatial structure when a physical one does not exist, or suffice.

Much like Medieval encyclopaedism; Renaissance thesaurus, wunderkammer, cornucopia, bibliotheca & musaeum; and Late Modern Era the Internet; theatre is a compilation of visual and textual forms which has served as reference points for humanist educational programs. Moreover, none of these phenomena have only existed as physical (tangible) entities, but foremost as mental and virtual categories. Their primary mission to collect texts, objects & information has been a cognitive activity that may be appropriated for social and cultural ends. In other words, the correlation between the theatre and the Internet is not only suitable.. it is inevitable.

In Kabbalah, Magic, and Science, The Cultural Universe of a Sixteenth-Century Jewish Physician, David Ruderman explains that “the basic planetary images” of (Camillo’s) Renaissance theatre “were talismans receiving astral power that could be channeled and operated through the agency of the theatre. By mastering the proportions of universal harmony whose memory was preserved in the theatre’s structure, the operator could harness the magical powers of the cosmos.”

And, what can be more magical than the experience of, literally, observing the creative soul of a group of artists travel across oceans and continents via the World Wide Web, in real time. This is such stuff as dreams are made on wherein a group of vibrant performers in Los Angeles can put on a comic book-flavoured adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth in Hollywood that may be seen by viewers from Seattle to Stuttgart and Singapore. Richmond who has worked in Europe & across the United States, describes his directing philosophy as an exploration of “space, time, physicality, and relationships in unique and creative ways.” In this spirit, Psittacus’ 21st century configuration of theatrum mundi turns the world into a theatrical community by attempting to challenge and blur ideological, local and temporal differences.

Just as Camillo wrote his text on his teatro della memoria in the future tense, Psittacus, too, awaits its wooden O wherein resident and visiting artists can generate one of the first large-scale fusions of the theatre with the full spectrum of new technology. “We propose taking over a raw, unused commercial space in downtown Los Angeles for a year,” Butelli explains passionately, “We will, then, retrofit it as a theatre with all the needed technological devices that will help us connect with our audiences around the globe.” Psittacus is determined to generate something quite revolutionary.

In a recent article in The Wall Street Journal, Clay Shirky writes, “There is no easy way to get through a media revolution of this magnitude; the task before us now is to experiment with new ways of using a medium that is social, ubiquitous and cheap, a medium that changes the landscape by distributing freedom of the press and freedom of assembly as widely as freedom of speech.” So, how does Psittacus plan to start its media revolution?

The company calls on all modern day talismans with stellar power who will channel their philanthropic might to the exploration of universal truths through the agency of the theatre. In simpler terms, the company needs all the financial help that it can receive. According to Butelli, much of the reason for the financial troubles that so many arts organizations are experiencing is “because they rely so heavily on a limited number of super wealthy donors who have been fueled by the stock market.” Psittacus’ funding model is to rely on smaller cumulative sources. To that end, the company is taking a number of assiduous measures that include joining KickStarter, which according to The New York Times is an “online site that helps creative people find support.”

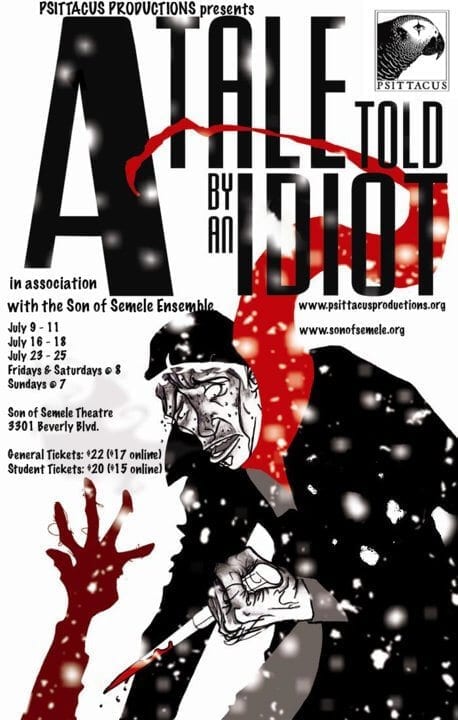

On June 18-20 and July 9-25, Psittacus begins its first season with A Tale Told By An Idiot; a new 60-minute stage adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Determined to make a most memorable first impression, Psittacus’ Macbeth is “a visually stunning textual and movement piece with a comic-book aesthetic and original techno score.” The live performance will be streamed over the Internet and shared via social networking sites during which viewers can engage in a real-time chat. Viewers Psittacus

Louis Butelli is promising to become to the American theatre what Jason Silva is to Singularity. Both Butelli and Silva are young, dynamic and extremely talented individuals whose infectious energy and passion for their respective fields enrapture their viewers. In fact, it is from Silva’s forthcoming documentary Turning Into Gods that I borrowed the above quote by Freeman Dyson, “In the future…a new generation of artists will be writing genomes the way that Blake and Byron wrote verses.” The future is, indeed, very near.