I met Maite van Dijk, Curator of Paintings at the Van Gogh Museum, early in October (2010) during an event that honored Dutch collectors and patrons. The highlighted included a talk by Marina Abramović the foundations of whose work were established in the Netherlands and supported by the Dutch government, in the late 1970’s. Ms. Van Dijk and I were joined by museum colleagues from the Rijkmuseum as we discussed the role of private patronage for public collecting institutions.

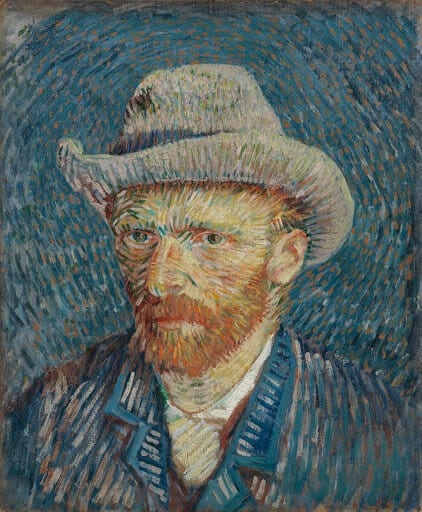

Homa Taj – Vincent van Gogh is perhaps one of the most famous yet least known artists in history. I suspect that, in many ways, educating the public in face of well-established, albeit mis-informed perceptions, is far more challenging than teaching them thing toward which they hold no prior prejudices. What is the biggest mis-conception about Van Gogh which you find yourself having to constantly correct?

Maite van Dijk – This would be the romantic concept that Van Gogh was an isolated artist, who created a very personal oeuvre far away from other artists. It contributes to the notion of Van Gogh as a genius – who did not need training nor artistic exchange or inspiration for his pictorial development. This is a very common misconception about Van Gogh’s practice. He might have been working alone at many moments in his career, but he was always in search for artistic collaborations and connections. While working in The Hague, for example at the beginning of his artistic career, he sought the advise of established and mature painters, and went on sketching excursions in the city with the young George Hendrik Breitner. In Paris, he found himself in the centre of modern art, where he met many upcoming artists, such as Gauguin, Signac,Bernard, Toulouse-Lautrec and Anquetin. He worked together with several of them. He had contacts – through Theo – with Camille Pissarro and Seurat. Van Gogh kept an intense correspondence withEmile Bernard, in which they exchanged their ideas on art and pictorial practices. And, Gauguin lived and worked with the Dutch artist in Arles.

In short, Van Gogh was very well informed about the artistic practices and movements around him, even when working alone. The condolence letters sent to Theo after Van Gogh’s death in 1890 are proof of his network: many important figures of the contemporary artistic community shared their sympathy with Theo. A letter by Camille Pissarro in our collection, is only one such an example. He wrote: “This morning we received the shocking news of the death of your poor brother. My son Lucien only had a few minutes to catch the train, in the hope of attending the funeral. I very much wanted to go too, but was unable to get there on time. I regret this very much, for I really felt a great affinity for your brother who had the spirit of an artist, and whose loss will be deeply felt by the younger generation! …I feel really sad for you, my dear friend, and you have my heartfelt sympathy.”

HTN – The foundations of the Van Gogh Museum are based on the artist’s oeuvre as well as his own collection of paintings which includes works by contemporary painters including, of course, Paul Gauguin. How would you describe Van Gogh’s taste in collecting?

MvD – It is impossible to discern between Vincent and Theo in matters of collecting. The two brothers established their art collection together. It is now very hard to identify which piece was intended for their personal collection, and which they intended to sell. Vincent started collecting prints in the 1870s, when he was working for the gallery Goupil & Cie. He bought inexpensive prints of contemporary paintings. He stimulated Theo to start collecting as well, and his taste was very much informed by Vincent’s choices. Vincent regularly exchanged prints, illustrated magazines and woodcuts with the Dutch artist Anthon van Rappard. When he moved to Paris in 1886, Vincent discovered Japanese prints. They greatly inspired him in artistic ways, but he also considered them good investment for the future.

His reasons for collecting were threefold: a matter of personal taste; artistic inspiration; and possible commercial benefits. Vincent and Theo were able to acquire several important pieces by contemporary artists. Before Vincent arrived in Paris, Theo had already discovered the impressionist artists, such as Degas, Pissarro and Monet, but Vincent introduced to him to the new avant-garde artists consisting of amongst others: Gauguin, Seurat, Bernard and Toulouse-Lautrec. They were able to acquire works by all of the above. Vincent sometimes exchanged his works for paintings by his friends, and Theo had good connections with artists through his profession as an art dealer.

HTN – …How would you classify, if you can, collectors of Van Gogh’s works? And, I don’t mean the recent (past 30+ years) investment purchases. I refer to collections that were formed in the first half of the last century and are now open to the public, for example, The Kröller-Müllers, or others.

MvD – The dissemination of Van Gogh’s work started soon after his death in 1890, in particular due to efforts of Theo’s widow, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, and the artist’s friend Emile Bernard. They organized exhibitions and published parts of his correspondences, and soon Jo realized that she needed to sell works from Van Gogh’s heritage to spread his name. Some works sold in the 1890s, but the sales really picked up at the beginning of the 20th century. The first paintings entered in museum collections around 1900. The first great collectors were based in Germany. The German Expressionists introduced this passion for Van Gogh, hailing Van Gogh as their precursor and the father of modern art. The Dutch were quick to follow by organizing early retrospectives thus spreading Van Gogh’s fame throughout his fatherland. One of the most important early collectors was Hélène Kröller-Müller who assembled a very important and large collection of paintings and drawings by Van Gogh. After the Van Gogh Museum, the Kröller-Müller Musemcontains the largest collection of his work in the world. Van Gogh is the centre of their collection, surrounded by a very impressive collection of early modern art. In general, it can be said that – like her – the early collectors of Van Gogh were champions of modern art, establishing impressive and cutting-edge collections in which Van Gogh was presented as the founding father of these new artistic directions.

HTN – The Van Gogh Museum actively collects works by various artists. Give us an idea of the types of works that you acquire and the basis on which you make these purchases? Perhaps, you wish to provide examples of most recent or ‘interesting’ acquisitions…

MvD – The mission of the museum is to make the life and work of Vincent van Gogh and the art of his time accessible. We need to show the cultural and artistic contexts in which Van Gogh worked – the artists that inspired him, his artistic connections, his friends – in order to enhance our understanding of his art. This comes back to the first question. Van Gogh was not an isolated artist, and we want to recreate the networks he was participating in and to exemplify the artistic exchanges he maintained. By doing this, we hope to clarify Van Gogh’s artistic ambitions and accomplishments. The basis for this was the family collection, the works of art collected by the brothers Van Gogh. This is a wonderful point of departure on which we are now building. Through the Mesdag Museum in The Hague – which falls under the administration of the Van Gogh Museum – we have access to a beautiful collection of painters from Barbizon and The Hague School that greatly influenced Van Gogh when he was starting out as a painter. Van Gogh actually saw some of these paintings and even commented on them in his letters. His stay in Paris, also, has been very crucial to Van Gogh’s artistic development. He encountered modern art which opened his eyes to new ways. For example, he briefly experimented with the pointillist technique introduced to him by Seurat, Pissarro and Signac. The systematic application of paint did not suit Van Gogh, but it did free his brushwork and introduced a certain rhythm to his paint application. Pictures by these painters can thus exemplify this development in Van Gogh’s art. The Dutch painter was not only introduced to new ways of painting in Paris but, also, to new motives. He was exposed to urban themes in French modern art, such as theatres, cafes and boulevards. Our recent acquisition of a night scène by Louis Anquetin beautifully illustrates this worldly part of Paris.

Our acquisition policy is thus centered around Van Gogh; acquisitions need to contribute to our understanding of Van Gogh’s art and life by creating these multifold contexts.

We are also expanding our collection to show the importance and influence of Van Gogh on artistic developments, such as German Expressionism and Fauvism. These artists were greatly inspired by Van Gogh, and their work illustrate his importance and relevance for modern art.

HTN – …Considering the astronomical prices that Van Gogh’s paintings fetch at auctions, I think that it is impossible for any Museum to acquire his works on the market. This leaves you/other museums with collectors & arts patrons as your only acquisition options. But, how on earth can you convince a collector to part with their multi (multi) million-dollar works?

MvD – First of all, as a museum we are not mainly looking for those multi million-dollar works. We have a large and very representative collection of Van Gogh’s work, containing paintings, drawings, prints and letters, covering all his artistic years. However, in this overview, we do have some gaps. An early watercolour from his The Hague period, for example. So we collect differently then most private collectors – we are looking for very specific pieces. We are not necessarily aiming for the most expensive Van Gogh on the market, but works that contribute to the stories we wish to tell with our collection. These works are not always out of our reach – we have been able to add important works by Van Gogh to our collection in recent years, such as an early drawing and his letters to his friend and fellow-artist Van Rappard. However, some of the works that we are interested in, are indeed sold at astronomical prices. We try to fill these gaps with long-term loans from private collectors. Fortunately, there are several collectors that feel connected to our museum and who wish to contribute to this institution. The benefit of being a monographic museum is that we have a very strong connection with people passionate about Van Gogh, and we can share and exchange knowledge, interests and expertise with this community.

HTN – What has been the most note-worthy (or memorable) endowment to the Museum by a private collector – individual or corporation?

MvD – The most note-worthy endowment to the Van Gogh Museum was of course the one that started the museum. The Van Gogh family decided to give the inheritance of Vincent and Theo van Gogh – consisting of the works by Van Gogh, his letters and the brother’s collection of art by other painters – on permanent loan to the Dutch government, with the condition that a special museum would be build to hold these collections. This is how the Van Gogh Museum came to be.

HTN – What types of collections sharing projects does the Van Gogh Museum engage with?

MvD – We work closely together with the Kröller-Müller Museum; we organize exhibitions on Van Gogh together (such as the one now in Japan), we exchange loans and research. We also collaborate with other international museums whose collections focus on the 19th century. For example, we have an agreement with the National Gallery in London to exchange yearly one work of our collections. This year we have a beautiful portrait by Toulouse-Lautrec from their collection, enforcing our presentation on Van Gogh’s direct circle.The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston is very generous in lending us an important painting by Millet – who was Van Gogh’s main inspiration.

HTN – We cannot talk about histories (present and past) of collecting without discussing the critical importance of scholarly research. I understand that two years ago, the Museum introduced the Ronald de Leeuw Research Grant, in honour of the Rijksmuseum’s former General Director. Can you tell me a bit about the purposes of this award and how it helps to advance your Museum’s mission?

MvD – The Van Gogh Museum is very active as a centre for scholarly research. The museum wants to contribute to the study of nineteenth-century art by stimulating and presenting in-depth research in general and research about the life and work of Vincent Van Gogh in particular. We initiate many research projects – yielding in exhibitions, publications, collection presentations etc. The annual Ronald de Leeuw Research Grant offers the opportunity to a talented researcher to conduct research on a subject pertaining to the museum’s field of collecting. The grant is intended as a lasting tribute to Ronald de Leeuw’s achievements as director of the Van Gogh Museum (1986-1996). During his time as director De Leeuw promoted the importance of research into 19th-century West European art history.

HTN – You support research and scholarship to deepen and expand our appreciation for the art of Vincent Van Gogh and his contemporaries… However, you still have to take into consideration the power of cinema and the ways in which it has perpetuated certain images of the artist in popular imagination – this goes back to my first question. So, what is the best (accurate) and the worst (erroneous) films that you have seen on Van Gogh? And, why?

MvD – The first that comes to mind is the seminal film Lust for Life. It is both the best and worst film on Van Gogh. It is such a classic, it contributes to all the myths pertaining Van Gogh. It has been very crucial in the popularization of Van Gogh and in how we perceive Van Gogh nowadays. Accurate films on Van Gogh are mostly documentaries, the museum has just released a new one. The DVD is entitled A life devoted to art, and documents Vincent van Gogh as an artist and person.

HTN – Speaking of cinema – the most recent exhibition at your museum is Illusions of Reality– Naturalist painting, photography and cinema, 1875-1918. It coincides with Vincent Van Gogh and Naturalism which examines Van Gogh’s own appreciation for naturalist painters. Can you explain the premises of these two shows…

Naturalist paintings were an important source of inspiration for Van Gogh. Their motives, especially the rural life, and their affinity with sentiment had an impact on Van Gogh’s own art. He was also an avid reader and a great admirer of the French naturalist writer Emile Zola. So to stage an exhibition on naturalism fits very well into our mission as a museum to show Van Gogh in the context of his time.

Illusions of reality also explores how artists used photography for their paintings, and how early film producers continuously reused the motives of these naturalist paintings as inspirations for their movies. They did not only use the subjects from naturalist art – scenes from daily life – but also pictorial aspects, such as composition, focussing, cutting off. The exhibition shows how photography and cinema around 1900 were based on the same premises as naturalist painting.

HTN – What are your & the Museum’s next big projects?

MvD – In spring 2011 we will have an exhibition on Picasso in Paris between 1900 and 1907. It will be a great overview of these early works, but also shows how the Spanish artist related to Van Gogh. Picasso was openly competing with Van Gogh’s rising fame and status as the father of modern art. This project will thus contribute to our understanding of Van Gogh’s influence – both pictorial and intellectual – on the next generation.

Our next big Van Gogh exhibition will be in 2013, entitled Van Gogh at Work. Over the last 15 years we have conducted extensive research into Van Gogh’s way of working, and how this relates to that of his contemporaries. We are researching for example how Van Gogh acquired his knowledge and inspiration, and where he bought his materials. The research is concentrated on Van Gogh himself, on artists with whom he actually came into contact (such as Mauve, Toulouse-Lautrec, Signac and Gauguin) and on artists with whose oeuvre and way of working he was well acquainted (Monticelli, Delacroix and Millet). This project is being undertaken in close cooperation with the Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage (ICN) and partner in science Shell Netherlands. All in all, more than 30 researchers from different disciplines in and outside the museum are currently working on this innovative research project, which will result in an exhibition and publication(s).