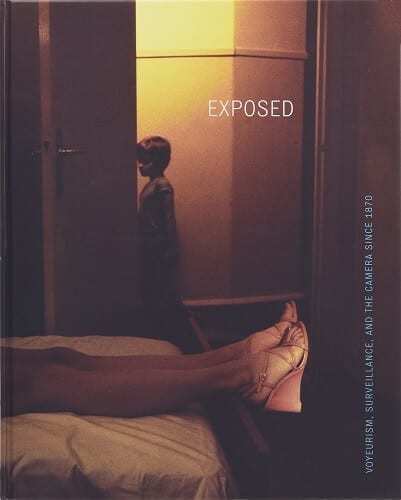

Early last week, I caught up with Sandra S. Phillips, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s Senior Curator of Photography, to discuss her institution’s forthcoming exhibition Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance, and the Camera Since 1870. The show, that was on display at Tate Modern, earlier this summer, will be on exhibit from October 30, 2010 until April 17, 2011. Dr. Phillips has been with SFMOMA’s Department of Photography, considered one of the most active in the country, since 1987. She was appointed Senior Curator of Photography, in 1999.

Homa Taj – How did the idea of curating an exhibition on Voyeurism and Surveillance come about; perhaps inspired by your 1997 exhibition, Police Pictures?

Sandra S. Phillips –You are entirely correct! I have been thinking about such a show for a long time, and it started when I finished the exhibition called Police Pictures: The Photograph as Document. It seemed to me that there was another way of seriously considering photography—what makes it so important in our lives—and that was the voyeuristic aspect of the medium. As time went on I also became interested in how this voyeuristic aspect merged into surveillance, and these are issues that affect us daily.

HT – SFMOMA’s geographic proximity to the Silicon Valley renders it one of the most suitable institutions to show an exhibition which addresses a century of ‘surveillance’ technologies…?

SP – I suppose you could say that, and indeed, there are works in the show which deal explicitly with the technologies of the Silicon Valley (one is called BIT plane, where a recording device is fitted to an unmanned small plane that flies over some of those companies that are very private). But I was just as interested to find a longer history, which turned out to be very revealing. I discovered that the idea of a right to privacy was initiated with the development of the small camera and film fast enough to capture real life in motion. That was 1870.

HT – Actually, I would say the same about London – the exhibition premiered at The Tate, earlier this summer – where there is an epidemic of CC TV presence across the city. How did you experience seeing the show, there (in that context – where you conscious of this reality, etc)?

SP – Yes, the folks in London were even more sensitized to this issue than we are, believe it or not. They are also especially protective of the way children are represented publicly. This is probably because of the sad case in Scotland where a child was abducted by two older children in a mall, and died. It was all captured on surveillance tapes.

HT – Speaking of technologies: what types are you employing to enhance visitors’ experiences, at the exhibition?

SP – There is a current blog, but most interesting to me are the representations of the works of two artists which deal with this aspect of the subject of surveillance – Julia Scher andMarie Sester. You will be able to follow this work on line. The Scher piece is really historical (as well as hysterical) – it was made around the time of our move into this building fifteen years ago. Marie Sester’s work consists of a spotlight fitted on the roof of the atrium, the large open, public space downstairs, when you enter the museum. It is guided by a robotic device that selects someone to follow – an unsuspecting visitor to the museum. It is wonderful and creepy.

HT – Based on your catalogue – which, by the way is quite beautiful – the show is at once densely scholarly and (often, though not always) entertaining. It appears to be a roller coaster ride of emotional experiences spanning the gamut between sensual and gruesome. Explain the curatorial challenges that you faced while creating such a dramatic (drama-laden) narrative – even though the exhibition does not follow a traditional narrative?

SP – Thanks for your compliments! Well, my essays really follow a train of thought: first you have the technology that permits you to take pictures easily and secretly, and that becomes street photography, an aspect of the medium still very much practiced. Then I wanted to explore spying on the forbidden—the first subject clearly was sex, the second had to be how we now have a whole segment of society that is interested in notoriety, and we follow celebrities who are both interested in maintaining a presumption of privacy while actually courting the public. Then it seemed to me—growing up in the sixties as I did—that seeing violence on television—the murder of Jack Kennedy, the vicious dogs attacking black students trying to integrate their schools, the Vietnamese monk who set himself on fire to protest what was happening in his country—that we might find the history of this interest in violence in photography and see what has happened to it. I do believe violence has terribly affected who were are. Then surveillance followed very naturally from that—it seemed logical and natural, like Hansel and Gretel picking up the breadcrumbs in the forest to find their way home.–

HT – Speaking of (non-)narratives, if we were to read Exposed as a cinematic story-board – which it can very well be – which film director do you think would best execute it? And, why?

SP – Well, one of my favorite directors was Arthur Penn, who certainly had the imagination and bravery to make this subject into a very interesting tale.

HT – The exhibition is broadly divided into five parts: The Unseen Photographer; Voyeurism and Desire; Celebrity and the Public Gaze; Witnessing Violence; and, Surveillance. If you had your choice of adding another or expanding upon one of the category(ies), what would that be? And, why?

SP – Since I have been hanging the show in San Francisco, I realize that the Surveillance section is actually rather diverse and complex—there is surveillance that deals with military spying, mainly from the air; there is surveillance that seeks to pierce a person’s privacy, there is political surveillance—I think I could very easily expand this category.

HT – You have exercised a great degree of curatorial courage in organizing a show of photography, at a museum of (fine) art, while including images by amateurs, journalists and governmental agencies. How were these choices made?

SP –Actually, our museum has been one of several that has taken a stand for the importance of non-Art photography, for want of a better description. I grew up in New York, and my first serious encounters with photography were at the Museum of Modern Art. You may know that John Szarkowski was deeply committed to finding great pictures no matter who made them—machines, children, amateurs, etc. I am not only interested in these as pictures, but as carriers of cultural information. I think sometimes it is helpful to look at this work as well as work made by people who were very self-conscious about making artful pictures, and see the continuum.

HT – I am perpetually intrigued by histories and methodologies of collecting. So, I would like to know whether there a diverse range of collectors who collect surveillance-type images? If so, what is the most popular theme/type: erotica, true crime, celebrity, etc?

SP –I actually have no idea. I am certain that there are tremendous quantities of erotic pictures—the trouble is (for me) that many are visually boring. I also found that once there was a form established for celebrity pictures, that people making them nowadays rarely make better ones than those made in the 19th century. I do know that when I got deep into police pictures there were a lot of people who had them—some of the strangest and most resonant photographs in that earlier show were from private people that got gradually revealed to me.

HT – I think that this exhibition’s theme is very unique in that it will be registered differently by different generations: the younger (twenty-something) visitors will relate very different to the aesthetics of surveillance, voyeurism and, even, mug shots since they have become normalized and popularized by mass media and social networks… (What are your thoughts on this?)

SP – The subject is so broad, so inclusive, so surprising and so relevant I think that it will interest many different kinds of people. At least I hope so!

HT – I can easily see any single, or pair of, theme(s) from this show be adapted for a more complete examination, a full exhibition. Which one(s) might that be, were you to pursue such a project (& why or why not)?

SP – As I mentioned, I think Surveillance really does deserve a deeper and more thorough examination. There was an earlier show in Germany, but an even more informed and deeper show could be made now.

Sandra Phillips on Exposed @ Tate Modern, Courtesy Tate Modern

HT – On the same day that Exposed opens (October 30th), Henri-Cartier Bresson: The Modern Century is also scheduled to open. How did this coincidence (or not?) happen? And, how do you see the two shows relating to one another?

SP – This was a complete coincidence, and since he plays a major role in my show we thought it would make perfect sense to have the shows both open at the same time. So did his widow, and also the curator of the Cartier-Bresson show.

HT – What is your next major project?

SP – I have a bunch of them under my belt!