Canadian-Israeli-American playwright and screenwriter, Oren Safdie, has architectural genomes running through his blood. The son of the internationally acclaimed Israeli-Canadian architect, Moshe Safdie, Oren grew up in one of the greatest architectural heritage sites in the world, Habitat ‘67, in Montreal, Quebec. He attended the Graduate School of Architecture at Columbia University before turning to writing. Oren is a playwright-in-residence at the prestigious NYC theatre, La MaMa E.T.C. and until recently was the Artistic Director of the Malibu Stage Co. in L.A. It was at the Malibu Stage where his now famous Private Jokes, Public Places first debuted before running Off-Broadway. Safdie’s next play, The Last Word, ran off-Broadway in 2007 and starred two-time Emmy Award Winner Daniel J. Travanti (“Hill Street Blues”). His other plays include West Bank, UK; Jews & Jesus; Fiddler Sub-Terrain, Smothers; and LA Compagnie which Oren developed into a ½-hour pilot for CBS. As a screenwriter, he scripted the film You Can Thank Me Laterstarring Ellen Burstyn and the Israeli film Bittersweet. Oren has written for Metropolis, Dwell, Beyond andThe New Republic. His most recent play, The Bilbao Effect, opened in May 2010 at the AIA (American Institute of Architects) Centre, in New York City.

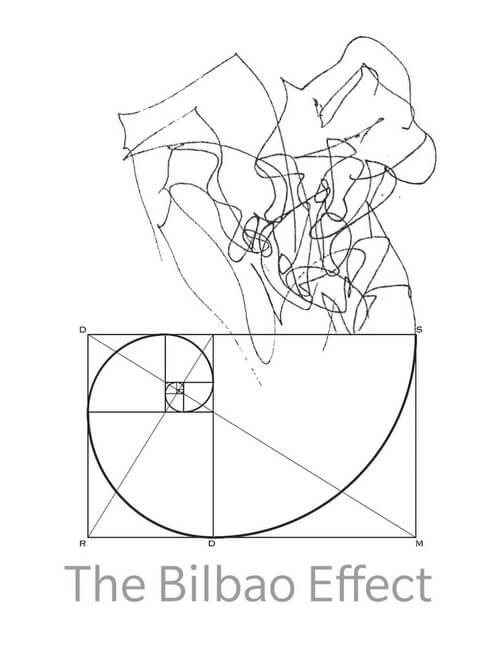

In the ”The Bilbao Effect,” Oren Safdie tackles the architectural myth – or is it reality? – inspired by Frank Gehry’s 1997 masterpiece: one of five branches of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Basque County, Spain. Gehry’s creation transformed the poor industrial port city of Bilbao into a must-see tourist destination. The success of Guggenheim Bilbao spurred other cities into hiring famous architects and giving them carte blanche to design even more spectacular buildings in hopes that the formula could be repeated. In The Bilbao Effect – the second play of a planned trilogy focusing on contemporary architecture — Erhardt Shlaminger is a world famous architect who faces censure by the American Institute of Architects, following accusations that his urban redevelopment project for Staten Island has led to a woman’s suicide. The play confronts controversial urban design issues that New Yorkers have recently encountered in Brooklyn as a result of the hotly-debated plans to redevelop the Atlantic Yards into an architecture-star mega-development. The Bilbao Effect explores whether architecture has become more of an art than a profession, and at what point the ethics of one field violate the principles of the other.

Homa Taj – You were raised with architectural genome running through your veins. When did you decide to deviate from the practice of architecture and become a writer?

I was in my last year at Columbia, and the University encouraged graduate students to take a course outside their discipline. For some reason, I took a playwriting course and won a competition for a short scene I wrote. But, perhaps, the seeds were planted in the summer in my second year: I had to write a paper for an architecture history class about the father/son Saarinan’s. For some reason, I flipped to the back of my notepad and started writing a train-of-thought rough novel about my childhood. I found power in the written word as a way of expressing what I wanted to say – more than design – and once I saw the words up on stage read by actors, I was won over.

HT – Academically speaking, you were trained both as an architect and a playwright. When visualizing your plays, do you envision them primarily in textual or spatial form?

It’s important to be able to use all the senses in theatre – to know when to call up those tools in order to give the play what it needs – but my plays do tend to be heavy on dialogue, which, hopefully, makes the physical moments all that more special and important. But I would say that playwriting is more like writing music to me. Words are notes, there are rhythms to spoken word and the back and forth banter, and if your ear is in tune, there are things that just don’t sound right. In fact, when I attend my own plays in previews, I sit behind the wall and listen to the words rather than watch. I can identify problems in the text or the acting a lot better that way. I think it’s what separates a playwright from a screenwriter or even a novelist. It’s different muscles.

HT – As with an architect, a playwright constructs a world which his or her characters occupy. Though architecture is, often, the manifestation of an ideal world… the space of a play is designed to accommodate the narrative, conflict and resolution of a story. Where do you begin?

I begin with characters, usually based on people I know. It’s then important to identify what it is each character needs. The needs from opposing characters should conflict. InPrivate Jokes Public Places it was a young student needing to convince the jury that she should be taken seriously. For the jurors, their needs became evident when the proposed design threatened to undercut their prestige, and so they became defensive and tried to take her down in order to maintain their status. Once I set up strong dynamics and interesting characters, I try and get out of the way and let the story tell itself. That said, unlike architecture, which has to deal with a specific site, I have endless possibilities, and I sometimes find myself imposing certain constraints to generate imaginative solutions – even if I end up breaking them. It also doesn’t hurt to choose a topic that you feel you desperately need to address. For me, hypocrisy is my target of choice.

HT – Many people that are raised under the shadows of powerful parents are often overwhelmed by their identities. So, they either run away from their influence or totally rebel against. You, however, seem to have taken inspiration from your father’s work …

It’s true that Private Jokes, Public Places owed some of its philosophy to my father’s writings, but the essence of the play was from my own experiences in architecture school and, I suppose, from growing up surrounded by architects and architecture where it’s in your face morning, noon and night. (We even lived in his building.) But if one looks at my next play The Bilbao Effect, or the third play in my architecture trilogy, which I’m presently writing, I think I approach the profession as both admirer and critic – some of which is agreeable with my father and some that conflicts with his beliefs. Now, if I write something that my father finds disturbing, does that mean I’m being rebellious? I would hope to think – and maybe I’m wrong – that I’m past the point where I am trying to do something other than express my feelings about something that moves me. But did it move me to see my father moved when he saw Private Jokes, Public Places? Of course. Likewise, I probably got a bit of a charge out of his negative reaction to The Bilbao Effect. I’m only human.

HT – What was it like to grow up in a contemporary heritage site – Habitat 67 (Montreal, Quebec)? And, what are your fondest (or remarkable) memories growing up there?

Growing up in Habitat ’67 was in many ways like living in a regular house – that is the feeling you got when actually in you’re apartment. We had three terraces, views of the city, St. Lawrence River and the old Expo ’67 site. These abandoned buildings served as our playgrounds. We’d bike over the bridge and scavenger through the old pavilions of the various countries. (The buildings weren’t torn down for some time as Montreal looked for ways to revive the Expo site.) Other than that, living in Habitat had mixed appeal. There was no other infrastructure in our area (shops, restaurants, schools, etc) as Habitat had to be scaled back from its original plan that envisioned it ten times the size. But the isolation also created a very strongly knit community. As the building’s paperboy – and the unofficial tour guide when my father was out of town -, I got to know every inch and everyone one in the building.

HT – It’s interesting that the title of Expo ’67 was based on Antoine de Saint Exupery’s autobiographical Terre des homes or “Man and his World” (1939). So, would you say that in some ways, the building embodies a double literary significance; that it is (i) the (auto)biography of (ii) a writer/philosopher. When growing up, were you aware of this literary (non-tangible) heritage – in addition to the monumental (tangible) heritage – of your ‘home’?

To be honest, I never heard of this inspiration for Habitat before. I always heard – and it is not hard to see – that Habitat was my father’s way of recreating his childhood home (Haifa, Israel) as he was torn away at a young age, after my grandfather decided his business prospects were better in Canada. The terracing, gardens – even being on the water – call to mind a Mediterranean city. Take an Israeli kid of 15 years old at the height of Nationalism, and tear him away from his friends and plop him down in snowy Canada, and something’s bound to happen. Longing for home is a powerful motivator.

HT – The first play in this trilogy is a comedy of academae – a favorite subject of mine! Private Jokes, Public Places premiered nearly a decade ago… Can you say a few words about it?

This play grew out of a ten-minute play I wrote while I was in architecture school. The architecture review at Columbia’s school of Architecture in the early 1990’s was particularly daunting as it was not unlikely to have Steven Holl, Kenneth Frampton, Robert Stern and/or Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas or a number of other titans sitting on your jury. It was a spectacle, and I always felt it lent itself to drama – especially when a student didn’t go quietly and roll over. (That was me!) But it was also interesting in that the jury became less about the project, and more about the famous architects doing battle amongst each other, and strutting their stuff to a public that was invited to come and watch. Another element that prompted me to pick up my 10-minute scene many years later and extend it into a full length play had to do with my own negative reviews I received for a spoof I wrote on Fiddler On The Roof called Fiddler Sub-Terrain, set in contemporary Montreal in the backdrop of Quebec politics. It brought back the feeling of putting something out there and being judged. (Also around the time, I received an alumni newsletter from the GSAPP and couldn’t understand any of the archi-babble language.) So, all these elements coming together at a specific time made me write Private Jokes, Public Places in 10 days. (I barely remember writing it – it was pure emotion.)

HT – Academic/institutional reform has been one of the main themes in your plays – at least the first two of this trilogy …

I see my three plays on architecture touching on different aspects of the field. Yes, Private Jokes, Public Places was about academia, and the notion that despite being an entity that should be open for learning and debate, it’s often very rigid and uncompromising. But, for me, The Bilbao Effect is about the professional practice of architecture and its moral and ethical responsibilities to the public. My next play, A False Solution, will tackle the creative side of architecture, exploring what influences an architect to design a building as they choose, including the politics, sex, ego and all those fun things that, hopefully, make a drama. With all these plays, architecture merely plays the background in dealing with societal issues. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be very exciting to watch. The Bilbao Effect was criticized by some for being a little to architecture-centric, and I’ve taken that criticism to heart in writing my new play. (I can’t ever forget that I’m a playwright first.)

HT – The Bilbao Effect, too, deals with issues that relate to the institution(s) of architecture. As a matter of fact, it literally takes place at the American Institute of Architects. Which came first, your desire to critique the institution (not the Institute) of architecture or was staging the play at the AIA an after thought?

The Bilbao Effect started with my series of satirical interviews I wrote for Metropolis Magazine, but also came about with my on-going question of whether architecture is following the right path – has it become too much of an art form without the art growing out from the design, much in the way a spider’s web is built for function, but is unequivocally beautiful in its structure and technology. (I suppose, I’m at heart a Frank Lloyd Wrightian.) So, how to deal with all these issues and bring in some of the characters I was working with in the magazine? A court trial seemed perfect. As Private Jokes, Public Places had moved off-Broadway and ran at the AIA Center in New York, I thought of the AIA New York site because I was familiar with the space, but it also represented an institution of authority and power. (I couldn’t really justify a court trial like this as a legal hearing, so it’s an internal hearing that’s been opened up to the public. ) I also went to their web site and looked up their code of ethics, and what is the procedure when one wants to file a complaint against an AIA member architect. From there, the imagination had to work out a way to make it a court trial open to the public – much in the same way the public was invited to be part of the proceeding in Private Jokes, Public Places, so I surmised that due to public pressure, the AIA has had to change their closed door policy and open the hearings to the public. Once the rules started getting stretched, it became part of the play where the structure and formality disintegrate until the proceedings resemble the Deconstructivist building that’s actually on trial. As the proceeding unravel and become more absurd, hopefully the audience begins to understand that the same level of absurdity in the architecture is being passed off as genius.

HT –At the heart of The Bilbao Effect lies the importance of challenging tradition – that is, not accepting it at face value but to examine it critically before accepting or rejecting it…

I’ve always been skeptical—hopefully in a positive way – that makes me research all sides and come up with my own conclusions rather than relying on “experts” or what is reported in the news from one side or the other. In any university, there is an overriding philosophy, whether you know it or not, and it just so happens that when I came into Columbia’s School of Architecture, there was a changing of the guard from one dean to the next. I didn’t exactly fit in with the new philosophy, and found that my approach was not celebrated because I was not creating structures and drawings that were as “fantastic” and acrobatic as some of my classmates. When you’re in the milieu of a trend and everyone else is going the other direction, it’s difficult to stick to your guns, especially when you’ve come to school to learn from experienced professors. But perhaps that was my real education in architecture school.

HT – It’s hard to read about architecture without thinking of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead (pub. 1946). Have you read the book, and if so, is there any correlation between Howard Roark and Erhardt Shlaminger?

Yes, I read the book quite a while ago, and also saw the movie. I think the two protagonists are quite the opposite though. Roark was loosely based on FLW, and he was an architect obsessed with design as a social statement. I don’t think today’s architects possess the same motivations, nor do I feel they would go the distance to protect the integrity of their design. It’s a sign of our times. But it’s also a comment on society. People have become too comfortable. I blame TV.

HT – Did you go to Bilbao to visit the Museum? (Whether yes or no:) How else did you study this ‘Effect’? In other words, what inspired you to write a play about this particular phenomenon?

I have not been to the museum, but I have been to various other new Deconstructivist museums, opera houses and concert halls. (I know Mr. Gehry doesn’t like being labelled as a Deconstructivist, but I’m not sure what else you’d call it.) But I suppose the Bilbao Effect became very evident to me when I was living in Toronto – a city desperately trying to find an architectural identity, and so insecure about being a world class city, that they totally fell into the trap, trying to lure name architects with splashy buildings in order to highlight the city. They’ve ended up with Libeskind’d ROM – one of the ugliest buildings I’ve ever seen. But another thing tipped my off while I was in London. It was reading a review in the Guardian of a new addition to the Denver Art Museum, also by Libeskind, and was struck by the praise for the building even though the architecture critic admitted that the building was probably terrible for housing any art. Then, of course, one only has to be in touch with the public and feel their resentment to all the new buildings coming up. They’re powerless to do anything about it.

HT – Have you ever met Frank Gehry? Also, do you know if Gehry or anyone from The Guggenheim has seen the play? If so, what are their responses?

I’ve met Mr. Gehry briefly. No, I don’t think he saw the play. But I also think it’s important for me to correct a misconception. Although The Bilbao Effect had many similarities with his Atlantic Shipyards project, and take the title from his building, it is much more critical of architects who have tried to imitate what he did. One of my favourite buildings is his Fred and Ginger building in Prague. But I do think when you blow up the scale of what he’s doing – such as the Atlantic Yards, or even M.I.T., it becomes irrational slice and dice for the mere pleasure of being different without philosophically justifying itself. When I was in architecture school, I also attended a lecture of Frank Gehry, before he got really really famous. He showed a highrise building that he was designing, and on the top was something that looked like a fold out newspaper. Asked how he came up with it, he explained that during the creative process someone put a folded up newspaper on the top and it looked interesting. I was a little struck by that – and not in a good way.

HT – What do you think of Gehry’s 2008 statement in which he declared that the notion that a single building can alter the fate of an entire region is… “B.S.”?

I tend to agree. I think the problem arises when a city or an architect sets out to transform an entire city with one building. That said, buildings are tourist attractions, and I’m not sure as many people would go to Pisa if the leaning tower wasn’t leaning.

HT – What did your father think of The Bilbao Effect? Moreover, what does he (&you) think of today’s Starchitects?

You’d have to ask my father, now that he’s seen the play. After he read it, he wasn’t very pleased. He was disturbed. In terms of today’ starchitects, hopefully that definition will change as more firms are becoming a collection of young architects. What came out of the field before the recession had a lot to do with our economic times, and the field’s need to put out recognizable figures to augment their profession. But hopefully, that has changed and we will not have the “signature” architecture where a city wants to get a “Gehry” or a “Hadid” as if they’re collecting art. Still, I do worry that as we go forward, and architects feel they have to stand out from the pack, we will continue to see projects that make a mockery of their surrounding and place importance on themselves. Instead of fitting in, recent architecture has been about standing out.

HT – What’s next in store for The Bilbao Effect? A Screenplay?

I don’t think this play would make a good film. But maybe a television series where architects have a secret plot to control the world. You’d need a super hero to counter them though, and I’m not sure that exists.