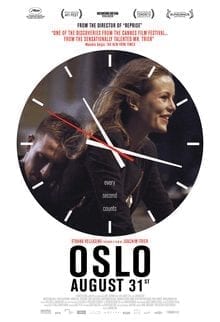

I met Norwegian filmmaker Joachim Trier at the 55th BFI London Film Festival. His latest feature OSLO August 31 is a story that takes place in one day in the life of a young recovering drug addict. On August 31, the film’s protagonist, Anders, takes a short leave from his treatment center to interview for a job and catch up with old friends in Oslo. As with Trier’s critically acclaimed Reprise (2006), Oslo is a softly stylized film with incisive attention to details including its palette and sound. Oslo August 31 was part of the Official Selection at Cannes Film Festival 2011, and is shortlisted as one of Norway’s top three submissions for the 2012 Academy Awards.

I met Norwegian filmmaker Joachim Trier at the 55th BFI London Film Festival. His latest feature OSLO August 31 is a story that takes place in one day in the life of a young recovering drug addict. On August 31, the film’s protagonist, Anders, takes a short leave from his treatment center to interview for a job and catch up with old friends in Oslo. As with Trier’s critically acclaimed Reprise (2006), Oslo is a softly stylized film with incisive attention to details including its palette and sound. Oslo August 31 was part of the Official Selection at Cannes Film Festival 2011, and is shortlisted as one of Norway’s top three submissions for the 2012 Academy Awards.

Homa Taj- Where do you find your aesthetic inspiration…? Where do you go? Do you go inside (yourself) or look without…?

Joachim Trier – You have different phases in the process of creating an intuition… That is what we strive to achieve as directors/ filmmakers. For me it all started with cinema. My love for the medium. The possibility and the fact that even though you could use lens the same lens, or the same location, even almost the same framing… if you come back the next day or a few days later, the mimetics of cinema create a new image. Very often it’s almost impossible to reproduce exactly the same thing anyway. So you’re working up against – well, most of the time, the way I work – some otherness in reality that you can’t control. When I started out I was very inspired by the more formalist approach to cinema in my early shorts. I thought that the more similar the image in my head was to the one on the screen the more successful my film would be. It’s a cliche but it’s actually true that that is not the case. My attitude, of course, has changed tremendously since I’ve discovered things through accidents, and how to create a climate around the camera and the way I film. So though there is quite a clear strategy, a visual thematic strategy, there are elements that I don’t control.

HT – Such as …?

JT – This is often the case in performance. I try to create something that it is subtle and nuanced … in performance but I am quite aware of how I frame it. Though, the more I work the more I’m interested in realism. In the sense not of reductive realism but in the sense that [Andrei] Tarkovsky, the great filmmaker, speaks about it. He says that you can walk down the street and see a man one day and if you try to put your camera in your eyes’ position and cast a guy that looks like him you capture nothing because you will carry with you on that day the notion that he reminded you of an old friend with whom you haven’t spoken to … or you might have quarreled with your girlfriend, etc. All these affect your mindset of an image in a film or the context of it. I’ve been more and more drawn to how that process figures in narrative. So an image never stands alone. It’s always in relation to something else. So, this is where I find the difference between a single photo or a single painting and film. You could of course say that in relation to other graphic arts that are done in series. Obviously. And, you can also see story-telling within within an [artist’s] oeuvre. But, it’s a different type of story-telling. It’s not consciously controlling time. So the temporal aspect of an image in cinema is quite unique. And, I think that that is also why I am drawn to cinema for inspiration for cinema. I obviously love painting. Who doesn’t? Or still-photography. For my recent film I look at a lot of old Magnum photographers and street photographers from America. I mean Grant’s ability to make something iconoclastic from everyday situations will always be inspiring to all filmmakers. But having said that, I seldom allude or reference directly a piece of art. But it’s all there as a part of the intuition.

HT – I mean particularly looking at (traditional visual) art for texture, for palette… more the sensuality of the image rather than its imitative mise-en-scene inspirational quality. For example, how do you decide that your brown palette makes more aesthetic sense as it hints toward burgundy, etc.?

JT – That is very interesting. We – my cinematographer Jakob Ihre and myself – are working a lot with neutrals, for this film, trying to create good skin tones and clear whites. Things that balance the other colour elements in the image because we find that neutrality is the hardest to achieve, almost.

HT – Almost like using black & white? It’s harder than b&W in some ways.

JT – Yes, but I don’t work in black & white any longer.

HT – Right. I also mean black & white is so inherently dramatic. Whereas if you use a neutral palette …it’s hardest to endow it with life and vibrancy.

JT – Well, by neutrality I also mean balance. I mean balancing the colours/palette. I have become more and more interested in how things work. How relative things are in life in terms of colour and mood. And, I still think that we need to understand that cinematic eye is so far removed from the human eye that to strive for a sense of human perception – and I don’t mean in a reductive scientific way, I mean it in an artistic way, hopefully – is the most personal approach you can have to cinema. Actually, trying to understand how you differ from other people, and how you see things. I mean how do you look at a face? For example, I believe there are infinite possibilities in terms of the close-up. But people often say, “Ah, close-ups are boring. They are for television.” But, actually close-ups in cinema are quite unique. You’ll never in any other art form, as far as I am aware, can see an eye that is nine feet tall. It’s closer than you’ll ever get in reality. So the close-up in cinema is a very unique form of expression.

HT – It defies realism because it’s impossible.

JT – Yes, exactly. So the fact is that in cinema, whatever you do, you end up with an abstraction of something, one that is seemingly mimetic. Or it seems to (imitate) reality. There is abstraction going on all the time. So, that play fascinates me. I don’t mean to be academic. But since we are talking in the context of visual arts, I allow myself to talk more freely. I think about this all the time. Also, when I choose space, I think of how will different lenses create different spaces out of the same actual space that you are filming. I always say this to directors, when I hear them saying, “Oh, I leave the lens to the DP [Director of Photography].” No! That’s your job. You must know lenses. That is one of your main tools for creating (e)motion and image. So, lenses are very important.

HT – Speaking of filmmakers as inspiration, you mentioned Tarkovsky, who is one of (if not ‘the’) my favourite filmmaker(s). If I had to save an archive from burning to the ground, I would sadly grab all the Tarkovsky’s and cry over the Bergman’s, and Kurosawa’s and the rest…

JT – [Laughs] Yes.

HN – And, it breaks my heart that they are available on DVD. I have all of them but never watched them… It is sublime.

JT – Yes. It is sublime, I agree with you.

HT – So, to whom do you turn when you look for inspiration in cinema? And, I don’t mean even when you are looking for something in particular …

JT – People whom I come back to when I lose faith sometimes are… Tarkovsky’s The Mirror (1975). Antonioni and Bressan, too. People that have a classical sense of cinema… just that breaking point when modernity meet classicism. These filmmakers have a classical yearning for something that goes outside mainstream cinema. There is also a radicality to these people that I find inspiring. Kubrick.

HT – Pasolini.

JT – Yes, absolutely. There are so many. I find filmmakers who struggle with convention yet have the craft to really take, to lift the big machine somewhere new in terms of its visual potential… very inspiring. Those are the ones whom I admire the most.

HN – These filmmakers whom you mention are very fluent in the craft & technicality of cinema… but there is also an extreme poetic sense to their work. By that I mean, that they have to search above and beyond tradition to come up with alternative techniques that express their vision because nothing that had been done before them can fulfill that.

JT – Exactly. I think that you are emphasizing an important aspect which is the fact that people like Eisenstein, Tarkovsky, and Hitchcock and Kubrick have been incredibly sophisticated technical directors. And, this is the things: you really need to know your tools. To be a film director is like being half-way between a military general and a poet. So you need both aspects, you need to be able to choreograph and push beyond the ambitions of the standard tripod and the camera in an aesthetic frame. You need to continually try to be creative about how to achieve images of movement. At the same time, to shield something definable, something that you are constantly worried will become too concrete and too banal… too explicit. It’s that balance of trying to get 200 people to get the same series of images which needs clarity. It needs mission. On the other hand, trying to create something that has subtlety, nuance and ambiguity, hopefully. I find that is the space of working as a film director for me. That is what I find fascinating time and time again.

HT – And, what about sound? Your films are very sound-sensitive…

JT – Yes [laughs]. I grew up with a father who was a sound designer. And, a recorder as well. So I think that that is a whole dimension of cinema that I am fascinated by. I find sound and the use of light very similar. You start sensing in a very primal way when things are being contrived …too much. And, that is fair enough. I like (sound & lighting) effects but sometimes I find it more sophisticated when filmmakers manage to take what is seemingly already there and know exactly where the breaking point for stylization lies. You can play with it but manage to find something that is expressive in a subtler, harder way than just the obvious effects.

HT – Well, it takes a great degree of aesthetic, emotional and artistic maturity to achieve what you just described. It takes quite some time in order to reach that level of sophistication that you are talking about.

JT – Sure, sure. I am still working hard to try to get somewhere.

HN – For example, in visual arts, especially contemporary art, everyone is obsessed with working with young artists. But, if I can help it, I don’t work with anyone under 45. I think that an artist just begins to realize what they are doing from their early ’40’s onward. And, from 40’s to the 70’s … that is actually the age range of artists with whom I like to work.

JT – That is interesting!!

HN – Well, because I think that even in their late 30’s, artists are still ‘getting there.’ But once they hit 43-44-45, then …

JT – I am 37 now so I hope to get there… [laughs].

HN – Oops [Laugh].

JT – [Laughs] That is good to know.

HN – This was the case even when I was in my 20’s…

JT – That is fascinating… [laughs]

HN – Well, I started in theatre and ended up in academia via film… I just came back from Frieze.

JT – So still a lot of people are doing appropriation art… [laughs]?

HN – Yes, plenty of happy, shiny stuff… And, they are not bio-degradable.

JT – I see this … art has become discursive which is painful for artists who fall outside the trend.

HN – Well, I was hoping that the recession would purge the market. But collectors are resorting to ‘known names’ who are the same ones who rose to prominence over the past 10-15 years. Ones who continue to create same mass-produced stuff (for the loss of a better word)… So, yes, I know many really great mid-career artists whose works are not being shown and who are dis-illusioned. They feel as if they have missed their chance because they are not young and hip anymore and that they don’t satisfy the art world’s paedophilic obsession with youth. And, arts patrons/ buyers don’t want to take risks with new people. So you have an entire generation of artists whose works may be lost to the system… Uppa. Guess I got the last word!

JT – [Laughs].