When societies face rupture, they don’t survive by forgetting who they are. They survive by learning how to see themselves anew.

Long before Iran opened a public museum, it cultivated something just as important: museum thinking. In the early decades of the 19th century, a small group of young Iranians from elite families traveled abroad and returned home as unusually careful observers of modern cultural life. Their travelogues and diaries weren’t dazzled so much as they were precise. They recorded where each museum came from, what it collected, how it expanded, how it was funded, who guarded the collections, and even how many visitors passed through its doors. Nearly a century before Iran founded its first public museum in 1916, the museum had already taken root in the Iranian imagination

One of the earliest figures in this story was Mirza Saleh Shirazi(1790-1845), who visited Britain in 1815 and documented his encounters with institutions such as the British Museum and the Ashmolean. For him and his contemporaries, a museum wasn’t simply a room of remarkable objects—it was a system: a way of organizing knowledge and making it visible. Many travelers referred to museums as ajayeb-khana, or “houses of wonder,” a phrase that echoed Europe’s wunderkammer while sounding entirely at home within Persian cultural life

Iran’s first museum space appeared later, but not as a public institution. Following his first European journey in the late 1860s, Nasser al-Din Shah (1831-1896), the fourth King of the Qajar Dynasty(1789-1925), established a Museum Hall (Talar-e Muze) within the Golestan Palace complex. Modeled on a European-style kunstkammer, it was private and highly restricted; few were permitted to view its collections. From the outset, museums—here as elsewhere—were bound up with access, authority, and the politics of display

By the late 19th century, Iranian intellectuals were articulating a far more expansive understanding of what museums could be. Mohammad Hasan Khan E’temad al-Saltana (1843-1896), court historian to Nasser al-Din Shah and a seasoned Europhile, described the museum as a place that holds “ancient objects, rarities, crafts,” and “valuable or memorable objects which have scientific qualities,” as well as “the arts, crafts, and discoveries of useful mysteries; and, of traditions and norms of every period.” He called the museum “the measure of wisdom” and “the mirror of perception,” a space that deepens collective understanding of history

This vision aligned Iran with a broader global shift. By the 1890s, museum professionals across Europe and North America were converging on a shared definition of the national museum. In 1896, G. Brown Goode, Director of the United States National Museum, defined its ultimate purpose as “the advancement of knowledge, and the preservation of specimens of works of art which hand down the history of the nation and the world.” Museums had become engines of national narration—and Iran was watching closely

After the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911), observation gave way to institution-building. In 1916, the Ministry of Education founded Iran’s first public museum, the Museum of Culture (Muze-ye Ma’aref), also referred to as the National Museum. Its founding ignited the proliferation of museums and cultural organizations across the country, laying the foundations for a new public life structured around heritage, education, and visibility

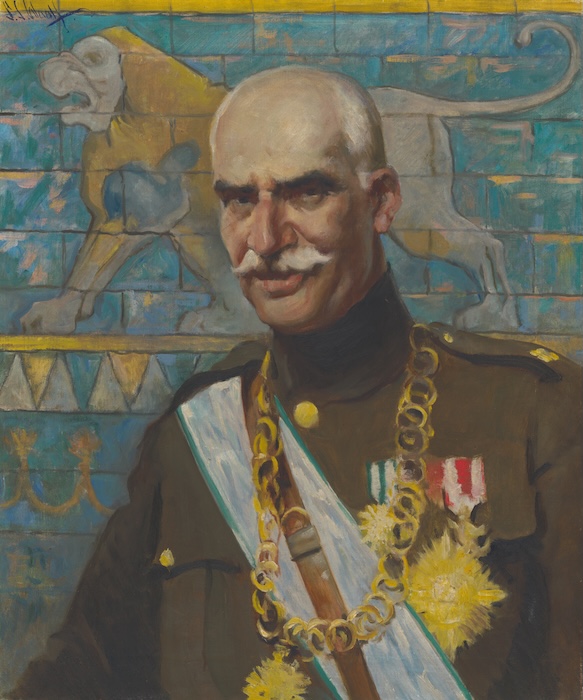

Under Reza Shah Pahlavi (b. 1878, r. 1921–1941), founder of the Pahlavi Dynasty (est. 1925-), museums became central to a fourfold state initiative—centralization, secularization, homogenization, and modernization—pursued not only through armies and laws, but also through cultural institutions. Museums formed public spaces where, as the thesis notes, “aesthetics and politics meet and champion one another,” reflecting a core priority: shaping the nation by giving form to a people and their culture. Heritage, in this moment, was neither passive nor nostalgic—it was strategic

The early 20th-century Iranian experience shows that cultural renewal isn’t a mood—it’s a method, deliberately built through institutions, policy, and public life. Iran’s story is therefore more than national history. It is a blueprint. It reminds us that when societies invest in ways of seeing, preserving, and sharing their past, they also build the capacity to imagine a future. In moments of rupture, culture does not merely survive—it leads.

Homa Taj Nasab is a scholar of museums and cultural institutions with doctoral research focused on the formation of modern museums in Iran. Her work bridges academic rigor and public cultural discourse, with a particular focus on heritage as a tool for renewal, identity formation, and future-making.